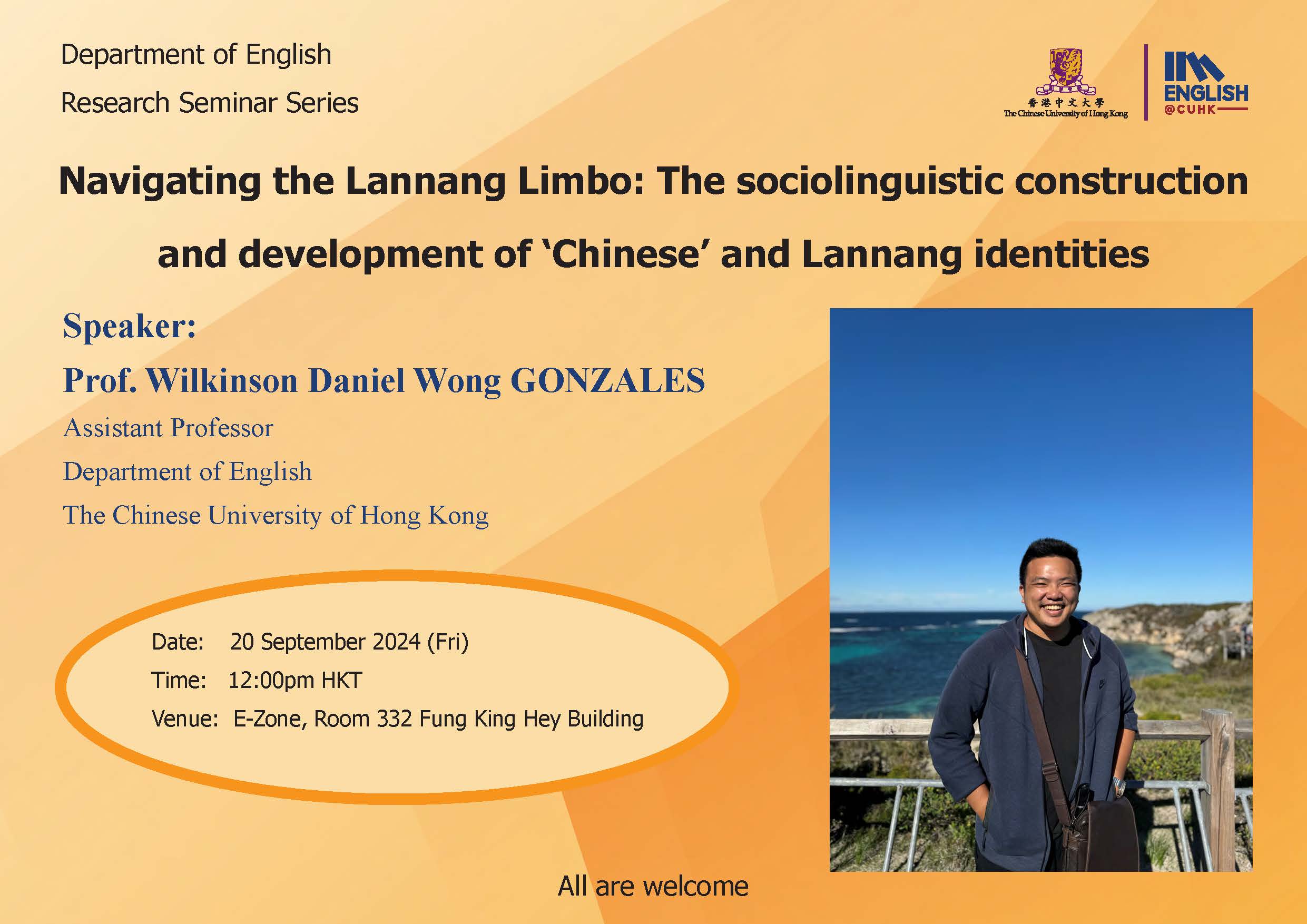

Navigating the Lannang Limbo: The sociolinguistic construction and development of ‘Chinese’ and Lannang identities

Prof. Wilkinson Daniel Wong GONZALES

Assistant Professor, Department of English

The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Abstract:

What does it mean to be ‘Chinese’ and speak ‘Chinese’ in the Philippines? To be ‘Lannang’? This presentation examines the role of Philippine Hokkien (also known as Lánnang-uè) within a Chinese heritage diasporic community in the Philippines: the multilingual Lannang community in metropolitan Manila. I focus on demonstrating how multilingual variability, combined with community ideologies, is used to negotiate ‘Chinese-ness’ – often associated with ‘Lannang-ness’ – and define ‘Chinese’ (language). Through ethnographic observations, interviews, and analysis of audio clips from the Lannang Corpus data collected between 2017 and 2023, this study sheds light on the linguistic and social dimensions of negotiating and constructing the ‘Chinese’ and/or Lannang identity.

Linguistically, the multilingual practices associated with Lánnang-uè exhibit predominantly Sinitic features in terms of structure and vocabulary. However, a significant portion of these linguistic elements shows non-Sinitic characteristics, including innovative derivations from Tagalog and English. Moreover, some language innovations are specific to the Lannang community, i.e., they cannot be traced back to any of the source languages. In other words, from the bottom-up, the findings suggest that Lánnang-uè does not neatly fall in the ‘Chinese’ and ‘non-Chinese’ categories.

Sociolinguistically, the community holds strong ideologies regarding who is considered ‘Chinese’ or ‘Lannang,’ often associated with speaking ‘Chinese’ or ‘Lánnang-uè.’ However, in practice, the definition of ‘Chinese’ or ‘Lannang’ appears arbitrary and fluid, as it has been observed to be inclusive of ‘pure’ Hokkien speakers as well as those engaging in mixed multilingual practices involving Hokkien. Certain speakers incorporate linguistic practices that could be considered non-Chinese in specific situations; however, they still identify themselves as speaking or using ‘Chinese’ or ‘Lánnang-uè.’ Others would claim that they use a ‘unique language’ or ‘mixed language’ distinct from Hokkien/Chinese. Variability is also present within individual speakers – there are situations where speakers who code-mix would claim to use ‘Chinese’ (e.g., within the local church) but would not necessarily use the term ‘Chinese’ to identify their language in other contexts (i.e., with foreigners).

Overall, the findings provide evidence of a locally negotiated ‘Chinese’ or Lannang language and identity that seems to have more social underpinnings than linguistic ones. They contribute to the existing literature on the topic. By exploring the intricate relationship between oral language practices, multilingual community ideologies, and the development or negotiation of Chinese-ness, I hope to offer some insight into the complex linguistic and social dynamics within this Hokkien heritage diasporic community.